The Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness:

The Cradle and Grave of the Rocky Mountain Locust

Jeffrey A. Lockwood

Professor of Natural Sciences & Humanities

Departments of Philosophy & Religious Studies and Visual & Literary Arts

University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY

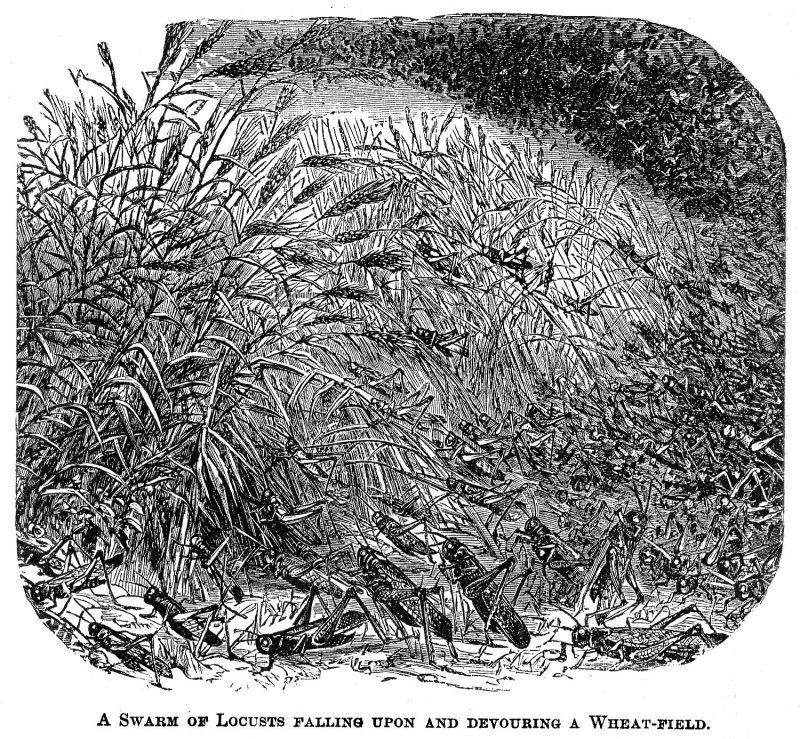

A blizzard sweeps over the horizon, and the sky fills with swirling flakes. But the fields are green, and the breeze is hot. As you wrestle with the incongruity, the sparkling snowflakes transform into voracious locusts — and your confusion transforms into terror. A fluttering insect strikes your face, then ten pelt your body, and soon hundreds envelope you in a vortex of papery wings. Through the maelstrom you see your crops melting away beneath a bristling blanket of locusts.

Imagine being in the midst of the largest congregation of animal life that the human race has ever known. Picture yourself in Plattsmouth, Nebraska, in the summer of 1875. A swarm of Rocky Mountain locusts flowed northward for five days, creating a biological eclipse of the sun. It is a superorganism composed of 3,500,000,000,000 individuals, outnumbering the human population on earth by a factor of 600 to 1. Before the year is up, subsistence agriculture across the Great Plains will be decimated and U.S. troops will be mobilized to distribute food, blankets and clothing to desperate pioneer families.

I came across an account of this staggering swarm in the Second Report of the U.S. Entomological Commission, published in 1880. By clocking the insects’ speed as they streamed overhead, and by telegraphing to surrounding towns, Dr. A.L. Child of the U.S. Signal Corps estimated that the swarm was 1,800 miles long and at least 110 miles wide. Had it been formed into a rectangle, this suffocating mass of insects would’ve blanketed Wyoming and Colorado.

Swarms like this — albeit on a smaller scale — are part of the life cycle of locusts around the world. At low population densities, these insects behave like typical grasshoppers, to which they are closely related. But when crowded, this insectan Dr. Jekyll transmogrifies into Mr. Hyde. Chemical cues from their feces and frequent disturbance of tiny hairs on their hind legs set off the metamorphosis. The changelings aggregate in unruly mobs, feed in preference to mating, grow longer wings and a darkened body, and irrupt into rapacious swarms.

It is as if whenever humans found that our neighborhoods smelled like sewers and that we were constantly jostled on the way to work, we abruptly changed into throngs of anxious, red-faced, sexually frustrated neurotics with voracious appetites and an inexplicable desire to buy a plane ticket. Perhaps locusts and humans have more in common than we suppose.

What entomologists refer to as the locust ‘phase change’ is a survival mechanism. In temperate ecosystems, these creatures swarm when droughts cause their verdant habitats to shrink, forcing the insects into crowded masses and signaling that it’s time to escape impending disaster. The swarms are like the Mongol hordes that once swept across the Asian steppes in search of new lands. And as with armies of Genghis Khan, the immense clouds of Rocky Mountain locusts are the subject of legend. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s On the Banks of Plum Creek revolves around the devastation wreaked by a locust swarm that descended on her family’s land:

The cloud was hailing grasshoppers. The cloud was grasshoppers. Their bodies hid the sun and made darkness. Their thin, large wings gleamed and glittered. The rasping whirring of their wings filled the whole air and they hit the ground and the house with the noise of a hailstorm. “Laura tried to beat them off. Their claws clung to her skin and her dress. They looked at her with bulging eyes, turning their heads this way and that … Grasshoppers covered the ground, there was not one bare bit to step on. Laura had to step on grasshoppers and they smashed squirming and slimy under her feet … “The wheat!” Pa shouted.

Today, this is hard to imagine; it sounds like an Alfred Hitchcock thriller with insects replacing birds. But if we find it difficult to envision such masses of life, it is even more challenging to grasp that within 30 years of Dr. Child’s account of the largest insect swarm ever recorded, this species disappeared — forever. The last living specimen of the Rocky Mountain locust was collected in 1902 on the Canadian prairie.

But if we pay careful attention, the Rocky Mountain locust has lessons to teach us about abundance and extinction, along with our tendency, as a species, to stumble like bulls through nature’s china shop. Perhaps most importantly, the locust has troubling implications for contemporary society and provides warnings about our future on a rapidly changing planet.

In 1986, I was hired as an insect ecologist at the University of Wyoming to explore the world of grasshoppers — a mission I pursued for 20 years before my own metamorphosis into a professor of natural sciences and humanities, serving the departments of philosophy and creative writing. No sane person would devote two decades to pursuing a subject that did not touch the heart and soul while stimulating the mind. I found that grasshoppers held mysteries worthy of this labor of love—and they provided lessons that catalyzed my move into the arts and humanities.

The science of entomology is an arcane discipline notwithstanding the 7,000 people who are members of the Entomological Society of America, which works out to about one scientist for every 2,000 species of insects. I understand not many people are impressed that I served as the executive director of The Orthopterists’ Society (Orthoptera being one of the 30 orders of insects and encompassing grasshoppers, locusts, crickets, katydids, and their lesser-known kin) or that I co-founded the Association for Applied Acridology International (acridology being the study of the family Acrididae which includes the grasshoppers and locusts). So, perhaps it’s not surprising that the tale of the Rocky Mountain locust was peripheral even within entomology. But the story had floated about for many years, and it fascinated me because of what was missing as much as what was contained.

Soon after arriving at the University of Wyoming, I learned that the generally accepted explanation for the locust’s demise was a vague conspiracy of vast ecological changes. Entomologists proposed that the disappearance of bison, the decline of fires set by Indians, and changes in climate had together altered the locust’s prairie habitats. But when I started digging through the evidence, these factors failed to provide a satisfactory theory.

The mystery was so intriguing, and the existing explanations so full of holes, that I was compelled to reopen the case. Besides, I had a lead on a bounty of clues that had scarcely been touched—or so I thought. Digging through old, obscure geological reports, I learned about the existence of “grasshopper glaciers” strung along the spine of the Rockies. Curious, I did more research, and learned that these glaciers were named for their contents — they had entombed wayward masses of what geologists took to be grasshoppers. But if the “grasshopper” corpses were actually locusts, they might provide a clue as to how these insects disappeared.

At first, it looked like the search for clues would be futile. My students and I started at Grasshopper Glacier above Cooke City, Montana, which had once been promoted as a tourist attraction, accessible by horse, and later, by jeep. The insects in that glacier were badly decomposed, as the ice had been melting for decades. Another Grasshopper Glacier in the Crazy Mountains yielded beautifully preserved grasshopper specimens, but they were no more than a few years old.

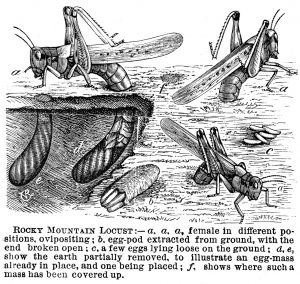

For the next two years, we searched the ice plastered on the flank of Beartooth Peak, near the Wyoming border. Again, we collected the mangled body parts of long-dead insects and honed our forensic skills. The fragments closely matched those of the Rocky Mountain locust, as we discovered that the mandibles of this species differ from its close relatives, much like how dental records allow forensic experts to identify dead humans. However, we lacked the definitive evidence that could only come from intact, whole bodies.

Finally, after four years of fruitless searching, we followed up on a tip from colleagues at Western Wyoming Community College—and we found the mother lode. High on Knife Point Glacier in the Wind River Mountains, with Gannett Peak looming at 13,800 feet in the distance, a frozen graveyard was emerging through the ice. The tiny bodies had been crushed, but many were intact. There was no doubt that these were the corpses of Melanoplus spretus. We’d found the locust.

——————————————————————————————————————

Full Content found in: Voices From Yellowstone’s Capstone: An Annotated Atlas of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness. Publication Pending.

Please consider making a donation to help bring this ambitious project to fruition

gf.me/u/ns2725

——————————————————————————————————————–

Setting aside the current wave of extinctions, the average species has a life expectancy of about 10 million years. As such, our lineage is in its adolescence — a time during which individuals of our species pay little heed to their own mortality. To teenagers, the notion of dying is irrelevant, a misperception contributing to irrational risk-taking that too often ends in accidental death.

Our species seems to be manifesting the same adolescent tendency at this point in its development. But there are older, wiser voices to be heard in our biological community, including that of the Rocky Mountain locust. A typical swarm contained a few billion insects, which is disconcertingly close to the current human population on the planet. We need only look back at the locusts that once blotted out the sun over Great Plains to realize that the future of a species is no brighter for its staggering abundance.

But, one might argue, human beings are the ultimate generalists. We are capable of adapting to a wide range of environmental challenges or, when times get tough, of moving to the next best place. However, the Rocky Mountain locust was also a generalist that consumed no fewer than 50 kinds of plants from more than a dozen different families, not to mention — when hunger demanded — leather, laundry and wool still on the sheep. In contrast, human beings derive most of our food from just three plant species — corn, wheat, and rice — found in a single family.

Moreover, if the body size of the Rocky Mountain locust was increased to that of a human, it would be capable of traveling 36,000 miles — approximately the circumference of the Earth. It appears that being a highly mobile generalist is little protection against extinction.

Still, the Rocky Mountain locust had an Achilles’ heel — the ecological bottleneck that allowed a small contingent of settlers equipped with simple agricultural implements to do them in. Humans don’t seem to have this sort of bottleneck. Or do we?

It’s not just the geological churning of Knife Point glacier that brought locusts back into the light. The ice fields of the Rocky Mountains are melting at a phenomenal rate. Based on our studies, Grasshopper Glacier north of Cooke City has receded 89 percent since 1940; the glacier in the Beartooth Mountains is 62 percent smaller now than in 1956; and the one in the Crazy Mountains diminished 90 percent in just 16 years.

Climate change may be as devastating to humanity as cows and plows were to the Rocky Mountain locust. As ecological processes on the planet change through human activity, our species will increasingly face direct and indirect hazards to our flourishing—and our survival. Rising sea levels and desertified landscapes are already creating climate refugees. Desperate people add to burgeoning populations in cities and slums, while nations fight for access to water and food. A warming planet will squeeze our species into ever diminishing lands of declining productivity—a socio-ecological bottleneck is on the horizon.

In troubled times, humans seek solace. We are drawn to our sacred spaces: churches, synagogues, temples and — for some of us — serene mountain valleys, where rivers cleanse our anxious minds. Just as the locust found a refuge where it could rest and revitalize, we need our sanctuaries, our tonic of wildness. But is it possible that these havens — wilderness preserves, ungrazed meadows, clear streams, snowcapped peaks — might prove to be psychological, even spiritual, bottlenecks?

A century ago, human alterations of the environment caused the demise of the Rocky Mountain locust, and today, the ghosts of these insects thawing from the ice warn us of an even more serious threat to the natural world. As the current environmental crisis exposes our past act of accidental destruction, one can only wonder what else we might learn from the Rocky Mountain locust if we listen carefully.

Copyrighted Material

____________________________________________

This essay is adapted from “The Death of the Super Hopper” in High Country News, February 3, 2003, with permission.