Essay by David Kallenbach;

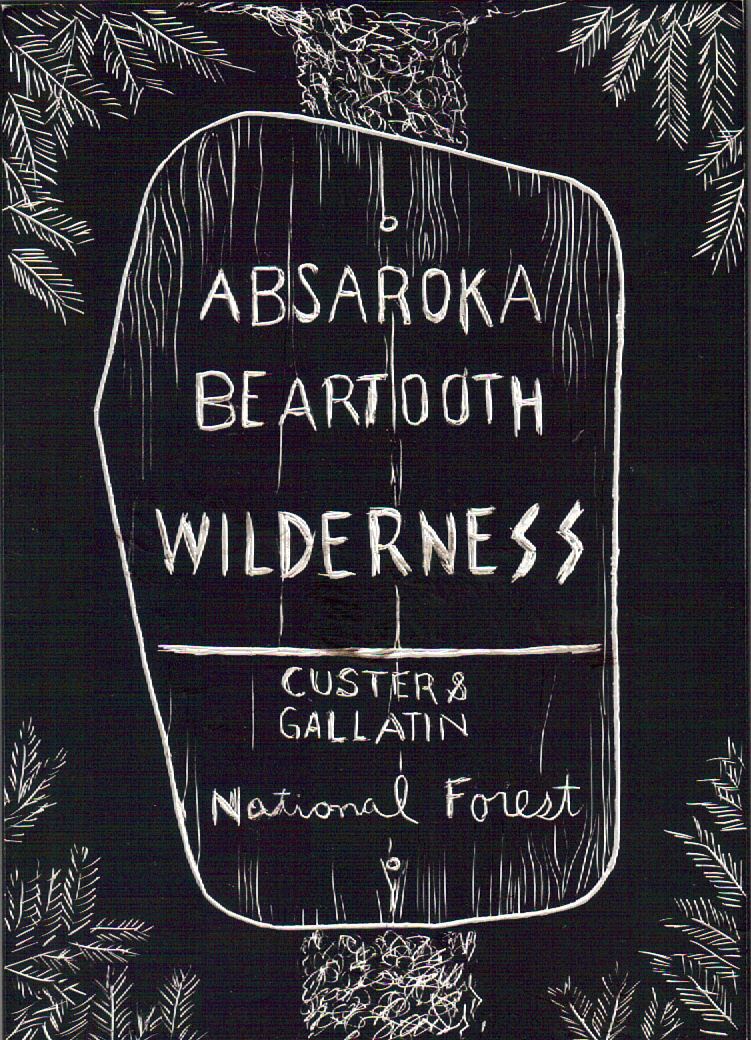

Art: etching by Ivan Kosorok;

Excerpt:

Meriwether Lewis, July 4th, 1805:

“the Mountains to the N. W. & W. of us are still entirely covered are white and glitter with the reflection of the sun. I do not beleive that the clouds which prevail at this season of the year reach the summits of those lofty mountains; and if they do the probability is that they deposit snow only for there has been no perceptible deminution of the snow which they contain since we first saw them. I have thought it probable that these mountains might have derived their appellation of shining Mountains, from their glittering appearance when the sun shines in certain directions on the snow which covers them.”

My own arrival in Montana in 1996 coincided with the release of Undaunted Courage, Stephen Ambrose’s popular re-exploration of the Lewis and Clark Expedition & the Corps of Discovery. That summer, working as an intern for Outward Bound in Montana, I had more than a few opportunities to actually stand in the places where Lewis and Clark stood on their journey to the Pacific—Lemhi Pass where Meriwether Lewis first gazed on the fearsome sight of hundreds of unexpected miles of rugged Rocky Mountain terrain separating his party from the Pacific Ocean; at Beaverhead Rock, where Sacagawea first realized she was back in her Shoshoni home-country from which she’d been abducted as a young girl; and Countryman’s Bluff outside of Columbus, Montana where William Clark surveyed from the Yellowstone River the brilliant enormity of the Beartooth Mountains on his way to a rendezvous with the rest of his party. Those moments left me with an odd tingling feeling, a notion that I was standing in the same places as the famous explorers nearly 200 years earlier.

But even more “déjà vu” than two people looking upon the same places, juxtaposed across 200 years of history, is the fact that after such a time these places were so monumentally unchanged from the days of Lewis and Clark. Climbing the bluff known as Pompey’s Pillar and witnessing the signature of “W. Clark, July 25th, 1806,” you can’t help but be struck by the quiet, natural beauty of that little stretch of Yellowstone River, remarkably little-changed, that signified the Corps of Discovery’s epic achievement in such a tangible way.

Everything that Lewis and Clark and their party looked upon in those days was wilderness. Today, wilderness places of the kind they witnessed are widely scattered and left completely intact only in a few places. The wilderness I stumbled upon in 1996—the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness–is one of those places.

How rare is it that we have wild places left that look remotely like they did 200 years ago?

Granite Peak, by Traute Parrie

(Content under development)