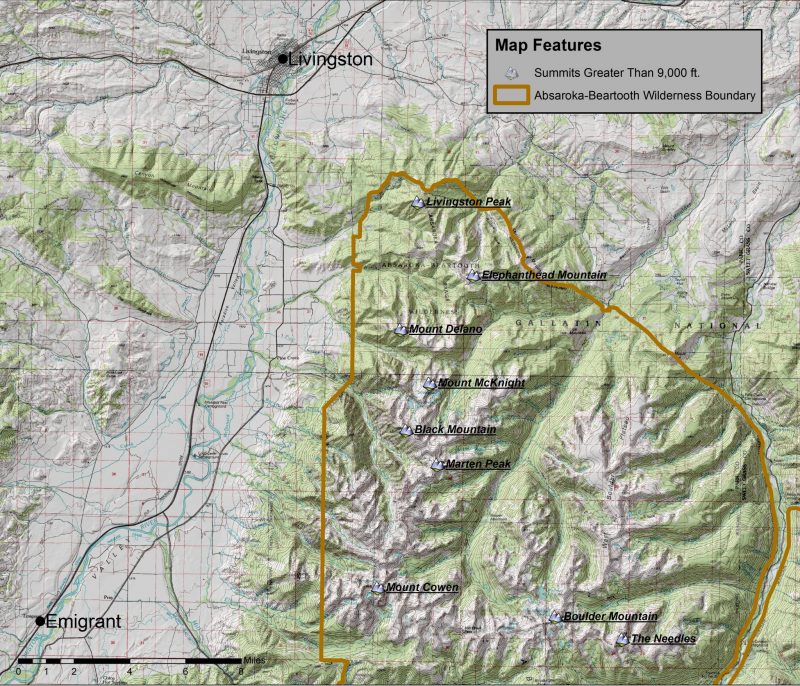

Yesterday I stood on top of Livingston Peak. It is a prominent marker for the river town of Livingston, Montana and its population of 7,500 people. It is the ample chest of what’s affably known as the Sleeping Giant, a series of foothills and mountains that dominate the vista from Main Street and almost anywhere else in town. At 9,313-feet above sea level, Livingston Peak is arguably a lesser mountain in the Absaroka Range, according to locals. Lesser, because in the Absarokas there are so many craggy mountains drawing up from the floor of Paradise Valley, spanning a chunk of southwest Montana and into Wyoming, that Livingston Peak is merely an entry level summit. It is the tip of a wilderness area with 22 unnamed peaks that have summits above 10,000 feet, and 27 peaks that are over 12,000 feet throughout 944,000 acres, including Montana’s highest point, 12,799-foot Granite Mountain.

Some might call it the beginning of the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness. Others might call it the end. When a mass of land spans nearly 1 million acres—a chunk of it high alpine terrain that most human feet will never touch—who is to say where the wilderness begins and where it ends?

Yet we do draw lines to define boundaries: we, the namers, the mappers, the keepers of place. To name a place is to give it relevance, meaning, and value by human measures. Since ancient times, people have sought to map the world, to name the places and lay claim to territory. It’s taken the form of a quest, a race, a war, a revolution, an expedition, a treaty, a map, a township, a road, a country, a globe. People have mapped rivers, mountains, oceans, continents, even outer space. But would any of it be less relevant if we knew these places, these riches, these realms by other names, or by no names at all?

The trail to Livingston Peak starts on National Forest Service land that borders private property. Popular with town kids, the trailhead is up seven miles of rutted and rocky county road that dead-ends at a green metal cattle gate where teenagers gather around a firepit at night with some secrecy away from the eyes of adults. Most of them don’t realize they are on the edge of wilderness. If they walked along the thin trail as it winds through mossy Douglas firs, Lodgepole pine and the flowery undergrowth that create a mottled shade, they might know how it really feels to get away from the world.

On the July afternoon of my hike, the wild delphiniums were as tall as my shoulders. The trail was distinct but overgrown with a confetti of wildflower colors. Arrowroot and Yarrow, Aster, Blue Bells, Geranium, Indian Paintbrush, Glacier Lily, Forget Me Not. Yellow, white, purple, exotic fuschia, orange, periwinkle. Usually I am adept at identifying flowers, but that day I lost track because there were so many different blooms.

After a mile, the trail crests a small hill where another gate marks a fork of National Forest property and a weathered wooden sign nailed to a fir announces the entrance to the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness in the Gallatin National Forest. A helpful hiker has added an arrow and the word “peak” in tiny knife-scrawled letters. My two dogs lead the way, turning left, at the arrow’s direction, we walked up. The big German Shepherd crashed through brush and deadfall, while the small terrier trotted behind her. Walking behind them, I scanned the hillside and then the forest. When my eyes locked with a set of yellow eyes, I froze.

The Great Grey Owl, disk-faced and massive was still as a stump, with feathers dappled like the bark of a tree. Unblinking and patient, just ten feet across the forest floor and inside the official wilderness boundary the owl waited for me to move on. I gawked in awe and challenged the bird to a staring contest. Minutes passed, the forest settled to silence, the owl stayed on its low perch. The return of my boisterous dogs broke the stillness as they romped back down the trail to find me. I blinked. The owl swiveled its head 180 degrees, spanned its wings and swooped out of sight. A win for the owl.

Does the owl know where this wilderness begins? I walked on and wondered, thinking that the trail on this side of the gate looks the same as the one I took from the car. Yet, I love the sign and how it tells me I am now entering a wild place. Since childhood, I have learned to love the moments of crossing invisible lines, from one state to the next: Wyoming to Montana to Idaho! From country to country: USA to Canada! Mexico to USA! And plain old National Forest to Wilderness! On the ground, boots on the trail, for the overflow of wild flowers and wild creatures it’s an arbitrary delineation, but on a map this line has distinction and weight enough to protect the land from roads, timber harvest, motorized vehicles and industrial development.

——————————————————————————————————————

Full Content found in: Voices From Yellowstone’s Capstone: An Annotated Atlas of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness. Publication Pending.

Please consider making a donation to help bring this ambitious project to fruition

gf.me/u/ns2725

——————————————————————————————————————–

Likewise, the unnamed peaks of the in the A-B Wilderness retain value not for their monikers, but for the fact that they are part of something much bigger, something unnameable that is, never the less, special.

It is the value in the great whole of wilderness, of a large interconnected ecosystem, that resolutely makes this corner of the continent special. While living here I have also hiked the wet granite trail to Pine Creek Lake. From the Mission Creek side of the Absarokas, I almost made it to the peak at Elephanthead Mountain before a late afternoon thunderstorm turned me back. Years ago, I struggled to the top of Emigrant Peak, the 10,919-foot sentinel of Paradise Valley that cups snow at its crest for most of the year. From Red Lodge I have bicycled up the Beartooth Pass and at its summit marveled over the expanse of Plateau with so many mountains and lakes I will never touch.

Before I knew there was a difference between National Forest and Wilderness, my Grandpa Norm took me trout fishing outside of Dubois, Wyoming in between the Wind River Mountains and the Absaroka Range. I was 14 and sullen. Grandpa’s idea of a dream trip meant I would miss out on a weekend with my friends, and most importantly then, I would not see my boyfriend for four whole days. The trip brought the dread of disconnection and I expressed it with adolescent power in the form of a crying tantrum. My grandfather never scolded me or faltered in his plans: We would drive four hours to a cabin in the mountains where there was no electricity or phone. We would hike. We would fish. We would cook our fish over an open fire. That was all he wanted to do. The thought of it made me despondent.

The remote mountains of Wyoming were the last place I wanted to be at 14, hormone-frenzied and otherwise tethered to my all-important social set. On the drive from Casper through Dubois I cried and slept. At the cabin I was disconsolate for the first 24 hours. What a wretched child; my mother even said so.

My grandfather’s patience, love of nature and stalwart affection for me eventually won out by the second morning. The aroma of pancakes sizzling in butter on cast iron snapped me out of my misery. From there all I remember is the clearest water and my first rainbow trout on the line. “Pull up, pull up!” Grandpa Norm called out with his net clutched as I set the hook from the creek bank. The next three days flew past and remain in my memory as some of the brightest spots of childhood.

Looking back to that point, I realize the Absaroka and the Beartooth Mountains have punctuated high points of many years. They have been the backdrop that has shaped childhood, adulthood, a family, a life.

My first experience in the Beartooth Mountains was at 20, working for a nonprofit research group to restock and support backcountry camps for scientific research expeditions in Yellowstone National Park. Our basecamp was Cooke City, Montana. My friend and I rolled into that remote town from Bozeman at midnight. It was mid-June and we’d finished finals at the university, packed up everything we owned in a Toyota truck with the plan to camp all summer. Our rendezvous point in Cooke was a tiny cabin at the edge of town. There was no address or phone number to reach the folks at the cabin, so when we arrived at that late hour we simply parked the truck on the side of the road and bedded down in back with sleeping bags. It was overcast that night, there were no stars visible and so dark we couldn’t see any buildings or houses. Exhausted, sleep came fast.

The frost of morning woke me before sun-up. I peeked out from my down sleeping bag to look up at a black silhouette in the pale sky. It took a few blinks to realize I was looking at a jagged outline of mountains, but when it registered, I was giddy with the beauty of those peaks. I wanted to experience their ruggedness, their alpine purity and learn more about them. Later, I realized that view was my first glimpse into the heart of the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness.

Since then, over three decades I have hiked, biked, ran, snowshoed and skied the trails along the toenails of the Absarokas, feeling like they are my backyard playground. The boundaries and politics of wilderness, of Yellowstone, of public land were not directly on my mind while I enjoyed these places daily. But I have intentionally raised children in these mountains, teaching them to leave no trace, to respect nature, to be forever curious. Through their childhoods my daughters have waded through the shallow, clear water of Pine Creek in August. They know how to build a fire, set up camp, and to be bear aware. They have bushwacked to harvest huckleberries in the South Fork of Deep Creek. They’ve run along the trail through wildfire burns on the way to Passage Falls in autumn. They have camped in winter.

Most of all, my daughters have learned to love nature. No matter what the trail is called, no matter whether a sign designates it to be protected, they have learned not to take wild places for granted. My greatest hope is that their generation will be one that not only keeps the backyard of the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness intact and strong, but that they will add to it, they will fight for it, so that generations afterward will be able to call it by its name forever regardless of where it ends or begins.