Essay by John Clayton;

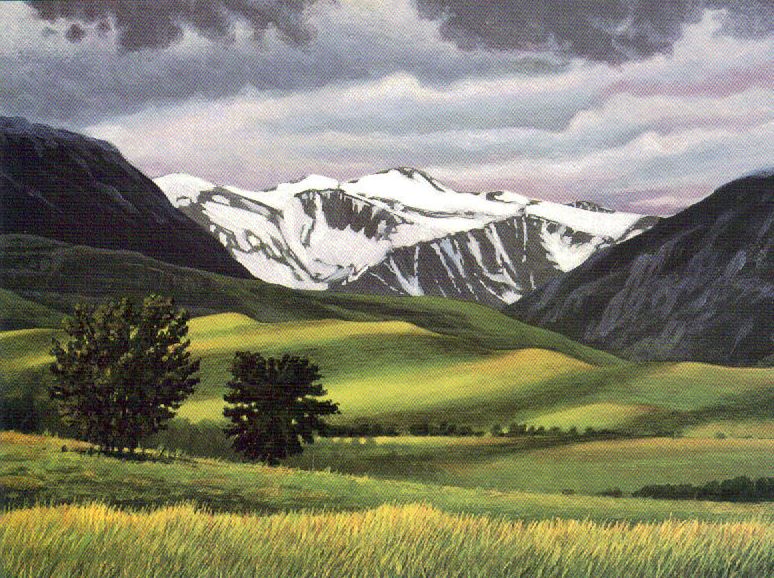

Art: “Beartooth East Rosebud”, by Monte Dolack;

Article originally published in High Desert Journal, April 2017;

I came for the scenery. I signed up as a trail maintenance volunteer in the Absaroka-Beartooth wilderness north of Yellowstone National Park because it gave me five days among blooming wildflowers, burbling streams, and evergreens swaying gently in the wind.

I came for the Pulaski. The dual-headed shovel/axe is a totem for forest crews throughout the West, but I’d never used one. If I learned how, the Pulaski could stand in for all the other tools—from carabiners to scythes—that people I admire have used to interact with their environment.

I came for the muscles swinging the Pulaski. I hadn’t worked on a trail crew when I was in my early 20s, and now, more than twice that age, I half-wished I had. As in a fantasy baseball camp, I sought the personal challenge of following old dreams plus the physical challenge of trying to merely keep up. As midlife crises go, I kept telling myself, this adventure was far cheaper than buying a Ferrari.

I came for the work my Pulaski achieved. With steady declines in Forest Service wilderness budgets, who will take care of our special places? The Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Foundation, sponsor of the trip, suggests that volunteers can tend the wilderness. Beyond political advocacy, we can put our muscles where our mouths are.

But in the end, more than any of these reasons, my great reward came from doing work in this particular place. I worked the wilderness—and thus embraced a contradiction.

* * *

The Wilderness Act and I date to the same year, 1964. My birth, to white middle-class religious intellectuals, was steeped in planning and tradition. I was named after my father’s father, my mother’s brother, and—all of these influences squeezed into a single name, as if my parents could bless their eldest son with an encapsulation of their lives to date—after my father’s first professional mentor, a gay man unlikely to name sons of his own. By contrast, the federal law creating Forest Service wilderness areas, though far longer in gestation, was more of a break with tradition. America’s family tree contained no notion of setting aside land to be unimproved, “untrammeled.” The land had always meant resources: timber, minerals, soil, grass, meat, waterpower. The land was a setting for people to work to extract those values. And now the Wilderness Act established preserves of land as something different. Even the name wilderness was new—in the 1930s, land with these characteristics had typically been described, even when being lauded, as primitive.

I love wilderness areas. I love that they’re not shrouded in old mining ruins, larded with fast food or curio shops, spidered with roads, or (I’ll own up to a prejudice) crammed with overweight tourists. I love the habitat they provide for wildlife. I love looking at rocks and lakes and mountains in wilderness areas because they feel so much like pure nature, because they bring me closer to a spiritual connection with a deeper world. I love wilderness even as I acknowledge some complicating factors: Driving there, with high-tech gear, means that I contribute to destroying nature in order to enjoy it. The few people I see are typically other privileged whitefolks. And the whole idea feels more cultural than environmental, smacking of the Garden of Eden.

It’s one of our culture’s deepest-rooted stories: how humans were banished from a place of glorious harmony because human nature dictates that we can’t help trashing a place. Authors of the Wilderness Act were guided, perhaps subconsciously, by a belief that America in 1491 had been a sort of Garden of Eden, now mostly ruined. So maybe we could banish ourselves from a few remote areas before it was too late? (In my understanding of theology, it’s a crazy notion, because the wilderness designation is a human construct, and thus it too is subject to original sin—surely flawed, perhaps fatally so.) To define lands as “untrammeled,” we banish not so much humans as the results of human work. No permanent structures, no motors, no mining or drilling or logging. It’s OK to play or pray in the wilderness; we have chosen to believe that the human quality that ruins the land is our capacity for hard and smart work, and our insistence that such work result in evident change to our surroundings.

As a preacher’s kid, I’d seen how much work went into organizing a worship service on the “work-free” Sabbath. And the wilderness is a similar illusion: somebody has to maintain the trails, count the animals, and police the miscreants. For a layperson to be invited backstage, to participate in the hidden work, felt like an honor, the equivalent of being named an altar boy.

* * *

Our crew basecamped in a wildflower-strewn, bug-infested meadow. From there we worked our way up the trail, walking farther every day to discover new sets of clogged water bars. Our primary responsibility was to clean or rebuild dozens of these half-buried logs that direct runoff away from a footpath. To do so, I chipped with a Pulaski and heaved with a shovel. I moved rocks and balanced logs. I manned one end of a crosscut saw, and felt the magical teamwork that inspired blades to slice a tree.

It all felt very satisfying, and a little bit transgressive. I spent some time pondering why. Was I reveling in the violation of activating my masculinity, in ways that society rarely rewards these days? No: women on the trip seemed to match me in both work and satisfaction. Today, working trail crew is not a particularly masculine activity. My friend David, who runs the foundation, reports that 45 percent of his volunteers are women. At the Student Conservation Association, which provides trail crew volunteers nationwide, 53 percent of participants in a recent survey of high school programs were female.

If it wasn’t a gender issue, maybe it was crossing class norms—was I activating my inner proletarian? Again the crew’s makeup suggests no: we were all relatively educated whites. On his earliest trips David would give an informal lecture, one evening over dinner, about the intellectual and spiritual importance of wilderness—but he quit because his audiences got bored. He was preaching to the choir.

Part of my satisfaction probably came from my midlife rekindling of athleticism, and I half-expected to be surrounded by aging Boomers droning on about their marathon sports and the gadgets that measured their fitness. But I was pleased to find that I was the oldest one on the trip. There were plenty of millennials, conforming to national trends: that’s the generation that most embraces voluntourism.

I concluded that the satisfying transgression had to be about religion. I was taking sides in a religious conflict. Compared to the conflicts that dominate today’s media—abortion, gay marriage, creationism—it was subtler and deeper, poking at the Protestant underpinnings that set the assumptions for 20th century upper-middle-class America.

* * *

With my Calvinist background, I tend to see life through work. I take pride in the quality of my work and the effort I put into it. To me, “you work hard” is as impressive a compliment as “you’re a nice person” or “you’re really good-looking.” I grew up surrounded by people who defined their lives through their occupations—teacher, pastor, engineer. In my 20s I thought I was shunning their view of traditional career paths by moving to a small town in Montana. But looking back I realize that I was choosing my own occupational life-identity, that of a freelance writer in the West.

Given that identity, I faced an expectation that I should write about the environment. But for decades I struggled to. Part of the problem, I now see, was that I saw so little work to celebrate in the culture of conservation. Thoreau famously had no job at Walden Pond. He and thousands of subsequent naturalists observed. They tried to appreciate the processes and systems of nature, and humans’ insignificant place in that grand scheme. Some of them used those insights to achieve spiritual renewal.

That does take work, of a kind: attention, focus, patience, intelligence, wisdom. But it’s work you can do in the shade. It’s not the kind of work—the physical manipulation of one’s surroundings—that Americans have traditionally valued. Which means that on some level it felt to me like cheating.

I was raised to see certain ideas in conflict: mind vs. body, intellectual work vs. physical work, appreciation of nature vs. manipulation of it. Which set of ideas is more valid? The communities that nurtured me favored the first—and believed that they led to spiritual enlightenment. In rebellion, I came to argue that this view was a deceit, a luxury available only when somebody else embraced the second. So I celebrated blue-collar workers and resented conservationists. Conservationists told me to “Get involved,” which I heard as “Become a political activist”—intellectual work. Or they told me to “donate”—hand over the fruits of my intellectual work so that someone else could do some other intellectual work. They told me to “get out in nature,” with the implication that I could count miles hiked as physical work—but with a leave-no-trace ethic dictating that I have zero effects on the surrounding environment. I had to exhaust myself without making a difference.

I wanted the second set of values, physical work and manipulation of nature, to also lead to spiritual enlightenment. I thought of the old wisdom: It’s not the reward, a contented person says, it’s the work itself. I preferred that version to my family’s Calvinist maxim, If a job’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well. But either way the value arises out of the mastery of the work’s tiny details, out of producing a high-quality change in the surrounding environment. Such as a well-washed window. Traditional notions of wilderness exclude window-washers, and my transgression was to be one.

* * *

I went to the wilderness and I worked to transform the environment around me. Our crew’s water bars made the trail safer and easier for hikers and hunters, while lessening impacts on the surrounding plants and animals. And we made it prettier—less braided, less rutted, less mud-choked—to create a more effective setting for a path to spiritual bliss. In retrospect I like to think such benefits consecrated our work. In the best tradition of religion and spirituality, they did so even as the work made us feel insignificant.

After all, our labors were fleeting. In another 10 or 20 years, our new water bars would again need replacing. We were overmatched by the power of nature, and without motors or concrete, we had one hand tied behind our back. I welcomed that challenge. Because I was there to feel the work, and through that work to know the landscape. To me, that physical knowledge spoke more meaningfully, more religiously, than being able to recite the Latin names of the surrounding trees. For my Thoreau-inspired New England ancestors, the formula for contentment had been nature plus knowledge. But on this trip I made it nature plus toil.

By lunchtime on the fourth day we had climbed to 9,000 feet. Here a meadow boasted arrowroot, penstemon, and lupine; Joan saw a bull elk in the distance and Martin wandered after it with his camera. I rested my aging muscles and looked off to the southwest, at Electric Peak, Mount Holmes, and Bunsen Peak inside the boundaries of Yellowstone. I ate a sandwich and snapped some photos. It was a grand scene and yet peaceful, the kind of view that people like to say is better when it’s “earned,” when you’ve walked to it instead of driving. When you’ve worked.

I felt like my earned value was even higher than that, because my work had transformed my surroundings.

Indeed, as for highlights of the day, feelings of peak contentment, that experience may come in second. Because late in the afternoon, walking back to camp through a thicket of spruce, we stepped across a log placed at a 45-degree angle with the trail, the area in front of it scooped into a gentle bowl that would cradle the surface water of the next storm off to the left, draining it away from the trail.

It was the results of work that David and I had performed earlier. Coming back across it, he said aloud—to himself, or to me, or to the world, it didn’t really matter, they all felt the same at that point—“Sure is a nice-looking water bar.”